The 20th century marked the decline of construction in stone, the victim of rising energy costs, wars that decimated a skilled and knowledgeable workforce, and the fashion for new materials. To understand this rapid decline and witness the change from structural to veneer, take a walk in the heart of the city of London.

The journey begins at Bank station, the site of architect Sir John Soane’s 19th-century Bank of England building, understood to be his finest work. Soane’s building, mostly demolished in the 1920s, is our reference of load-bearing masonry. The building was constructed in Portland Stone brought to the site on barges. Utilising the full strength of limestone, it showed a complete understanding and potential of the material by engineers, makers, and the architect.

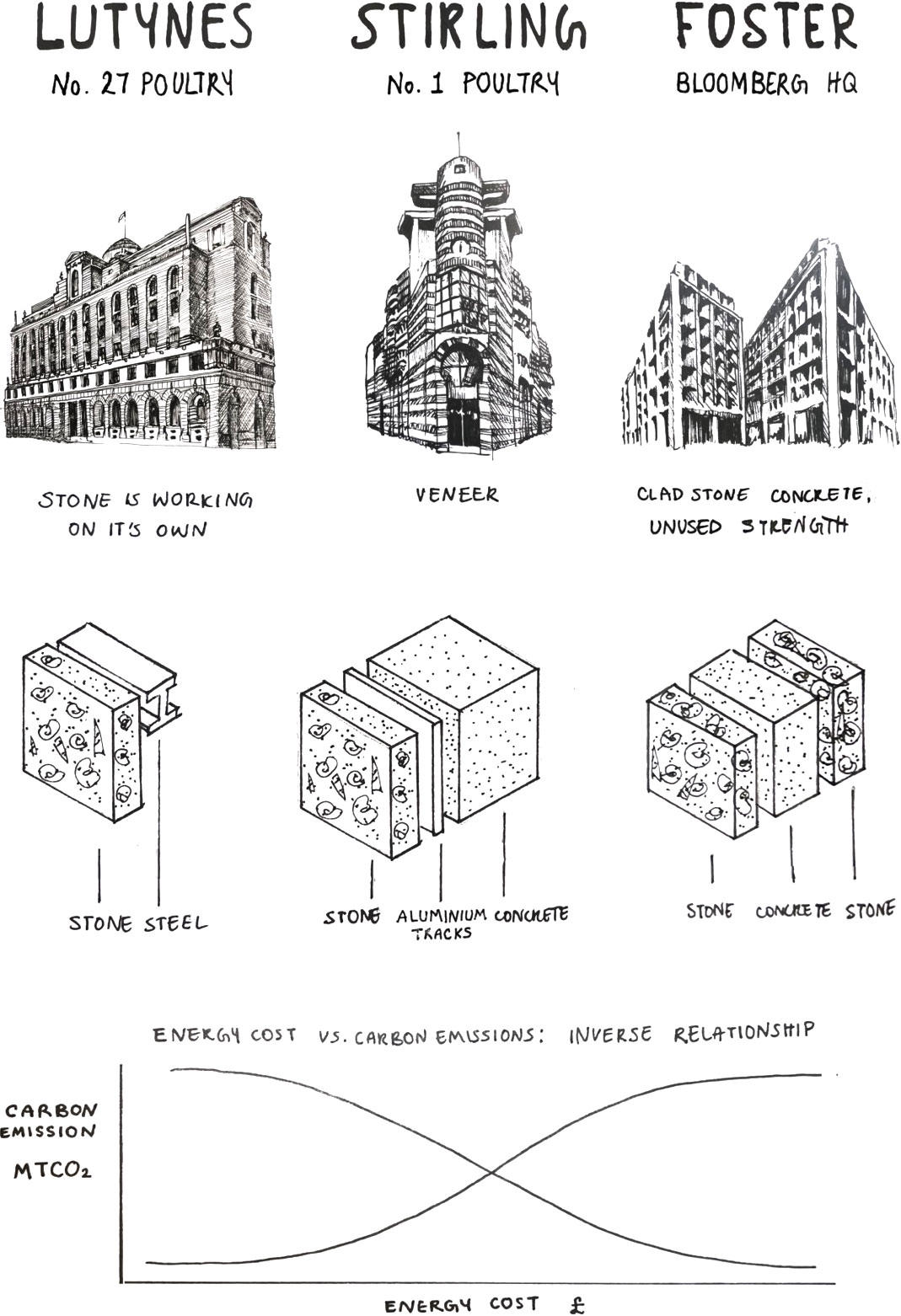

27 Poultry Lane by Edwin Luytens is another story. Built in 1924 with a steel structure, the engineers’ material of choice in Post-War Britain, steel was seen as easy to specify and control during its manufacture. The stone is now a self-supporting structure acting as a screen with a classical vocabulary. Across the street stands the iconic Postmodern No.1 Poultry by James Stirling, designed in 1985 and completed twelve years later, in 1997. Its pink and cream sandstone from Australia and the UK is only between 30mm and 50mm thick—a veneer hooked on stainless steel fasteners— a solid concrete shell embellished with a mineral make-up.

Lack of certification and codes ensures stone is left out of the materials conversation. During the late 20th century, architecture was not always concerned by the environmental impact or reuse of material. Across the road sits a behemoth of a building, the Bloomberg Headquarters by Foster and Partners completed in 2017, an exoskeleton of large Yorkshire sandstone pieces, patiently selected and fabricated off-site, then intricately connected to a structural concrete core. A tight embrace of two structural materials, leaving a legacy of wasted material and intensive fossil fuel use.

In the centre of London, Lutyens, Stirling and Foster wanted a heart made of stone, but built only a skin. However, their desire to use stone proves that architects and clients still want stone buildings as a symbol of authenticity, reassurance, and legacy. In the story of structural stone, the material can either push the limits of new technological developments or fall victim to progress and fashion. As we move towards more responsible construction methods, being both frugal and conscientious, stone, the low environmental impact material of excellence, just might be the solution.

Stone wall build ups and energy cost vs emissions, © The Stone Collective, illustration by Sofia Naseem

Stone wall build ups and energy cost vs emissions, © The Stone Collective, illustration by Sofia Naseem