Completed in 2017, 15 Clerkenwell Close by Amin Taha’s Groupwork demonstrated the architectural and structural potential of stone, elevating the material from thin cladding to true structure. Nestled amongst the buff London stock bricks of Clerkenwell, Clerkenwell Close’s stone ‘beam and post’ exo-skeleton almost became its undoing with Islington Council threatening demolition. The uncertainty ended with the planning inspector finding in favour of Amin Taha, agreeing the building was in line with the original design bar the rough and smooth finishes to the stone. It was agreed that the Council had broken several points of law in sanctioning the demolition order. In the intervening years the building has gone on to achieve wide acclaim for its striking use of limestone and could be said to have heralded ‘the new stone age’.

Groupwork collaborated with stonemason Pierre Bidaud of the Stonemasonry Company to realise Clerkenwell Close. When asked about the potential of constructing a five-storey building in stone, Pierre pointed out that up until the early 20th century historic London was built in load bearing stone.

Groupwork’s latest project, now rising on Finchley Road, extends the practice’s investigation into structural masonry at an unprecedented scale. The mixed-use residential building comprises three buildings - with the highest reaching ten-storeys - that form a complete stone skeleton of over 400 Larvikite beams and columns, produced by Lundhs Quarry, Norway. Each element was precision engineered before being shipped to London and craned into place. In total, 494 pieces amounting to 410 cubic metres of stone were produced over eight months.

Finchley Road, South View. Render by Groupwork

Finchley Road, South View. Render by Groupwork

Beyond its tectonic logic, recognisable as a striking sibling to Clerkenwell Close, the building establishes stone as a viable low-carbon alternative to steel and concrete. Groupwork calculates an embodied carbon saving of 80% compared to steel with stone cladding, and 55% compared to reinforced concrete structures. Unlike conventional post-and-panel systems, the frame here is also façade, eliminating redundancies in the construction process as well as minimising construction time and reducing material wastage.

Finchley Road construction. Image credits: Groupwork

Finchley Road construction. Image credits: Groupwork

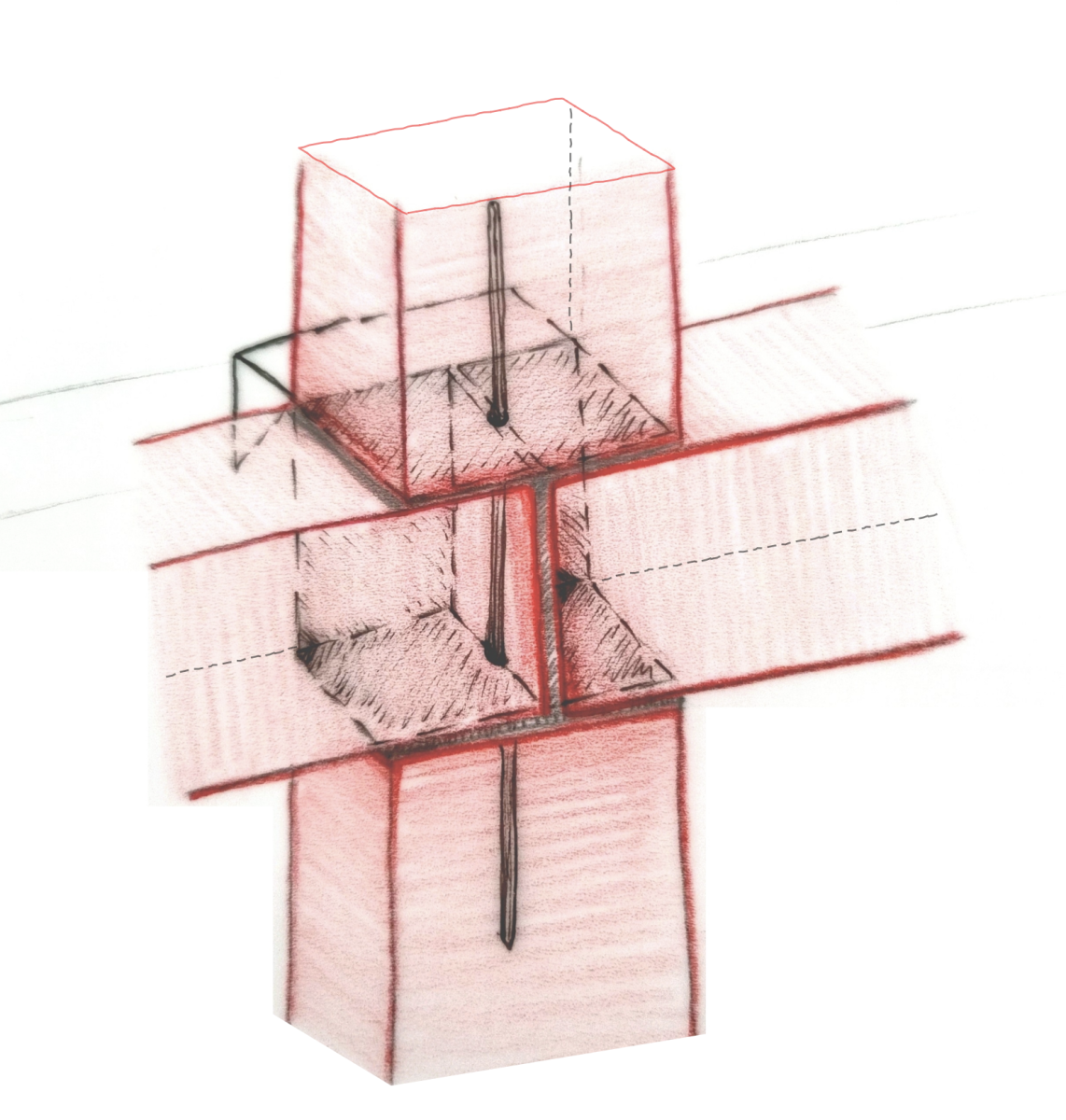

The project demanded structural ingenuity. Having worked closely with Groupwork on Clerkenwell Close, engineers Webb Yates provided Structural and MEP expertise. A sway-frame system was designed with load-bearing stone components acting simultaneously in compression and in resistance to lateral forces. Lead engineer Eleonora Regni describes several challenges including the inclined columns in all three buildings and the design of the connections for the stone elements. Conversations with stone supplier and installer ensured the best solution for the connections, minimising dowels in the columns. The stone is strong, and drilling is slow and expensive, the introduction of braces in the structure minimised the number of dowels needed.

Eleonora explains how the boundary pushing project necessitated new ways of working ; "designing the fixed connections between the stone beams and stone columns was particularly challenging, as there were no clear precedents for this type of solution. The connection was developed through close collaboration with the stone supplier to achieve both structural performance and buildability, while also minimising fabrication and installation costs." Webb Yates constructed and tested a full-scale prototype to ensure it could safely resist the design loads. As Eleonora notes; "this was further complicated by the presence of inclined columns, which required bespoke solutions to prevent sliding and ensure stability."

Originally specified using Italian basalt, the scheme switched to Larvikite, selected for its exceptional compressive strength; over three times that of concrete. The stone, quarried directly at source with shipping via a port close to the quarry, underscores not only durability but material integrity in sourcing and fabrication.

Larvikite beams and columns on the construction site. Image credits: Webb Yates

Larvikite beams and columns on the construction site. Image credits: Webb Yates

The site is small and close to a train station. Lift load limitations affected stone size with elements needing to be split and assembled on site. Prefabricated stone blocks used for the building’s lift shafts and risers contributed to the construction feasibility on Finchley Road’s confined urban site.

Ben Ayling, Business Development Manager for Lundhs in the UK is keen to stress the suitability of stone for structural use. Ben says "concrete has become the default for structural applications, but in many cases natural stone would not only perform better, it would also carry a fraction of the embodied carbon. Larvikite, for example, is exceptionally well suited to larger load-bearing structures thanks to its strength, durability, and low environmental impact." He believes Groupwork’s Finchley Road project shows how a return to stone can deliver both performance and sustainability in modern construction.

Larvikite beams and columns. Image credits: Lundhs

Larvikite beams and columns. Image credits: Lundhs

Groupwork’s Finchley Road stands as more than a residential block: it is a research-led proof of concept, bringing stone back to the centre of structural design. As Amin reflects, this may only be the precursor to far greater experiments: an 80-storey seismic-resistant stone and timber tower is now on the drawing board.

Topping out ceremony with architects Groupwork, engineers Webb Yates and contractors Ernest Park.

Topping out ceremony with architects Groupwork, engineers Webb Yates and contractors Ernest Park.

Vanessa Norwood is a curator and consultant for the built environment advocating for low-carbon architecture and materials.